National Water Center, Eureka Springs, Arkansas

National Water Center, Eureka Springs, AR

Updated: April 2014 Contact: Contact: NWC

Contents ©1999-2014 by National Water Center. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cool, Clear Water . . . An Unlimited Supply?

by Denise M. Sammons

As a child, it was nothing short of magical ...the elixir of princesses and wizards, the fountain of youth sought by conquistadors. Later, I simply took it for granted as the most available thirst-quencher on a hot day. It bubbled from fountains near my two-room schoolhouse, gushed from spouts over horse tanks and sustained farm ponds dotting the countryside. But when my life led me away to the city, I mourned its absence and carried it off by the jug full from my visits home. No water on earth could compare to the cold, clear, fresh-flowing artesian well water of my roots.

The name "artesian" comes from the Artios region of northern France where such wells were first noted by monks in the twelfth century. However, the Chinese had used this concept many centuries before Christ, driving bamboo castings down hundreds of feet into the ground to obtain water. As this task often required generations to complete, they were called "grandfather wells." Numerous artesian basins worldwide have since been tapped.

The concept of the artesian well is beautifully simple. Gravity and the most basic laws of physics apply.

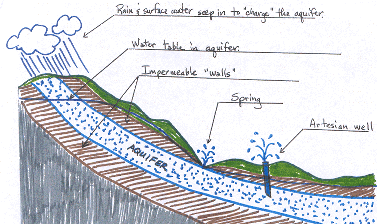

In areas where rainfall seeps underground between two layers of impermeable rock or clay, an aquifer is formed. An aquifer is a porous layer of rock filled with water up to the level of the water table (the highest level of water saturation in the ground).

In areas where rainfall seeps underground between two layers of impermeable rock or clay, an aquifer is formed. An aquifer is a porous layer of rock filled with water up to the level of the water table (the highest level of water saturation in the ground).

Where an aquifer slopes, the force of gravity on upper levels of water presses on water lower down. Its impermeable "walls" maintain this pressure. An artesian well pierces the walls of the aquifer below the water table, and the pressure from the weight of the water above this level forces the water out of the well. The difference in elevation between the water table and the point the well enters the aquifer determines the pressure of the well. As water from this source flows indefinitely under its own hydrostatic pressure, it is also known as a "flowing well." Likewise, springs occur where the surface of the ground naturally taps into the aquifer below the water table.

In areas where a sloping aquifer occurs fairly close to the surface, artesian wells can be placed quickly and inexpensively, if the upper wall of the aquifer is soft material such as clay. Just two men with a small water pump and sections of pipe can tap such a well by hand in a single day. The water pump is used to force water down the pipe, washing away debris and soil as the pipe is worked into the ground. Once the aquifer is reached, water flows by the force of gravity as described above, and the end of the pipe is plugged with weighted material to keep large debris from entering. The lowest section of pipe is fenestrated, allowing water into the pipe but keeping gravel and rock out. A cool, pure drink now awaits the laborers, refreshing them after their day's work!

Many artesian aquifers exist throughout the world. The largest artesian system is under Queensland, Australia. This much-used aquifer fills from rainfall in the Great Dividing Range, and runs beneath the arid surface of the Simpson Desert. In North America, artesian systems supply water to many East Coast cities and the Great Plains. In the Midwest, a great sandstone layer is sandwiched between two impermeable rock layers, coming to the surface in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Rain and surface runoff seep into the aquifer, which curves underground across several states.

Rainfall in the Sandhills of Nebraska replenishes the flowing wells of my youth. This small aquifer is held under pressure by a layer of clay just eighty feet below the surface, making it accessible to even the poorest Depression-era rancher.

Artesian well water is renowned for its purity and marketed widely on this basis, but its perfection is now in question.

As surface water filters through the porous material of aquifers, many impurities are removed. However, as man forces the land to produce larger crops at a faster pace, pesticides and fertilizers contaminate our surface water. Waste from livestock feedlots adds increasing levels of nitrates, which can eventually pollute the ground water. (It is estimated that 10,000 cattle can cause water quality problems equivalent to those caused by a city of 45,000!) In 1984, a survey by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) showed that out of 124,000 wells, 24,000 had elevated nitrate levels, and 8,000 were above recommended health limits. World Resources 1988-1989 states that nitrates may cause fetal malformations, blood poisoning in infants, hypertension in children and gastric cancers in adults.

Nature has its own remedies for natural pollutants, but her processes require years. She struggles to keep up with the increased burden of man-made waste, and her proficiency can no longer be taken for granted.

Due to its accessibility and reputed freshness, artesian water is often exploited. Overuse lowers the water table, depletes the aquifers and eventually creates an unreliable water source. The Black Hills aquifer is one such example. As demands on this water supply have increased, rainfall has not kept up. One well near Pierre, South Dakota on the Missouri River reportedly dropped 300 feet in 35 years, and many wells supplied by that aquifer have suffered diminished pressure and rate of flow. In shallow aquifers, even one pump-driven irrigation system could dry up numerous artesian wells.

My father has lived his 72 years in the fertile, flowing well country of north central Nebraska. I asked him for his perspective on the meaning of artesian water for him and his family through the years. "Mostly, it's been a simple, cheap water source. Most folks have five or 6 wells on their property, supplying fish ponds and cattle tanks. We've never had to chop ice for the cattle in winter, and a cool drink is never far away in the hot summer. . . The water stays at about 52 degrees year round, and it's soft and clean." Does he feel that any threats exist for his wells? "Lately, nitrates are showing up in small amounts on water tests, probably from fertilizers and manure run-off, but it's still pretty pure. And I don't think we're at risk of our wells going dry, unless someone tries to put in a center pivot around here."

Artesian wells . . . flowing wells of cool, clear water. Perhaps they do indeed possess a sort of magic, a figurative fountain of youth. For they, and the countryside they quench, draw me back to my source to sink my own family's roots in the same well-watered soil.